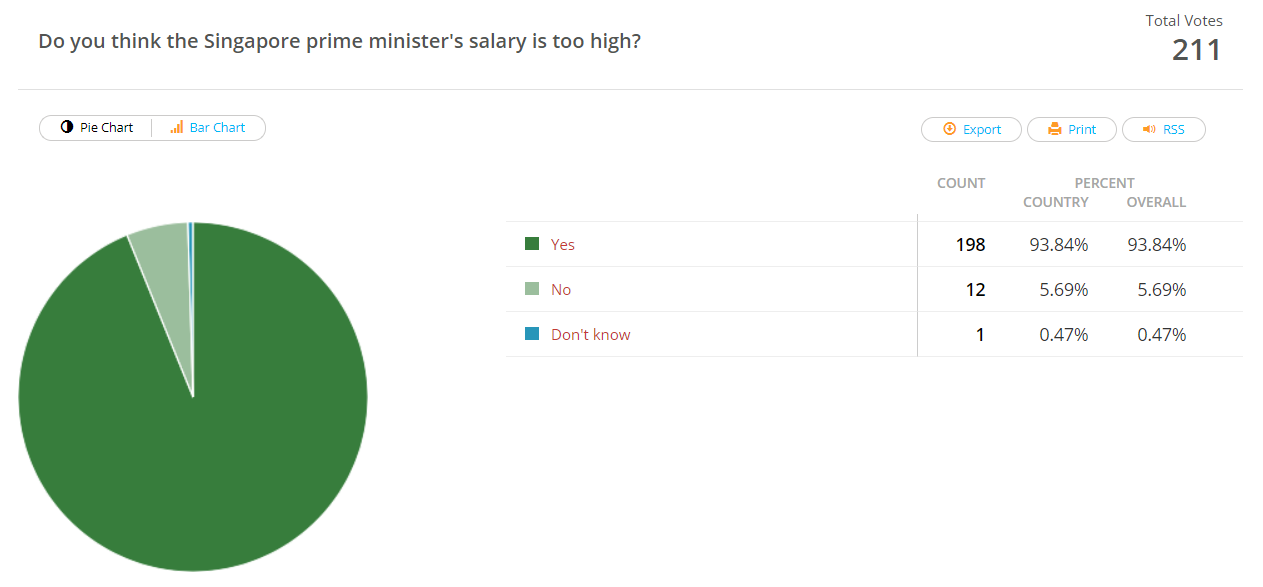

Over the last few years, the Singapore government has never been fully transparent with Singaporeans on how much salaries the Singapore prime minister and ministers are earning.

A month ago, on 10 September 2018, the Worker’s Party asked in parliament how much bonuses Singapore’s ministers are earning. However, the prime minister chose not to give a complete answer. On 17 September 2018, the Singapore government then accused Singaporeans of making false estimates but still refused to provide full transparent and open figures on how much the ministerial salaries are. Finally, on 1 October 2018, facing mounting pressure the deputy prime minister provided some further figures which allowed Singaporeans to make better estimates. However, the government still refused to provide the figures of the total salaries of the prime minister and ministers. Worse still, there is a special bonus that the prime minister and ministers get to earn, which has no stated limit, which means that theoretically, there is no limit as to how much the prime minister and ministers can earn. Read on to learn more.

Below, I have compiled the Facebook posts I have made on this issue (in chronological order), with the closest estimates we have on the prime minister’s and ministers’ salaries, and what the People’s Action Party (PAP) ruling regime still has not been transparent with Singaporean’s about.

*****

On 10 September, the Worker’s Party asked a question on how much total bonuses the ministers are getting.

Below is a calculation of the total salary of the Singapore deputy prime minister (DPM), based on the DPM’s response on 10 September:

- The stated Annual Salary of the Singapore DPM is S$1.87 million (including a 13th-month bonus, 1 month AVC, 3 months PB & 3 months NB).

- Assuming that he got the average performance bonus of 4.1 months in 2017, this means that his performance bonus was S$383,350 in 2017.

- All the ministers get a National Bonus (NB) of up to 6 months. Based on the formula to calculate the National Bonus (NB), they would have gotten 4.5 months of NB last year. The DPM would have gotten S$420,750. His NB bonus is enough to buy a HDB flat (see formula here).

- All the ministers also get a 13th-month annual allowance. This is an additional S$187,000 for the DPM.

- All the ministers also get an annual variable component of 0 to 1.5 months. Under the Stated Salaries, they get 1 month, which would give the DPM another S$187,000.

- In total, the DPM (and the other ministers) received a total bonus/allowance/AVC of at least 9.6 months.

In total, the Singapore DPM would have earned at least S$2.02 million last year. This is nearly 2 times his base salary.

>>>>>

For the prime minister, he does not get a performance bonus because it is claimed that “there is no one to assess his individual performance”. (Shouldn’t his performance be assessed by you – his boss?)

So, what does he get? He gets 2 times the National Bonus (up to 12 months). Here’s the breakdown.

- The stated Annual Salary of the Singapore prime minister is S$2.2 million (including a 13th-month bonus, 1 month AVC, 3 months PB & 3 months NB).

- His 13th-month annual allowance is S$220,000.

- His AVC of 1 month under the stated Annual Salaries would be another S$220,000.

- The prime minister’s NB is twice as high as the other ministers, so he would have gotten 9 months of NB bonus last year. This would be S$990,000. His NB bonus alone is nearly 2 times the salary of the president of the United States.

- In total, the prime minister received a total bonus/allowance/AVC of at least 11 months.

In total, the Singapore prime minister would have earned at least S$2.53 million.

But this is not even it.

All the ministers also can get an additional Special Variable Payment. There is no stated limit to this payment.

>>>>>

In Singapore, there are still more than 7% of Singapore residents who earn less than S$1,000 (and as many as 20% when including the foreign workforce). Most of them might have zero bonus.

The prime minister earns at least 11 months of bonus.

The Singapore prime minister earns 202 times what they earn.

In fact, the prime minister gets to earn S$1,000 in just less an hour.

If you earn S$2,000 a month, the prime minister just takes less than 2 hours to earn what you earn. 26.5% of Singapore resident workers earn less than this (43.7% when including the foreign workforce).

If you earn S$3,000 a month, the prime minister just takes less than 3 hours to earn what you earn. 43.1% of Singapore resident workers earn less than this (as many as 50% when including the foreign workforce).

And yet, the prime minister asks you to cut down on your expenses during his speech at the National Day Rally.

In one month, the prime minister would earn S$210,833 a month. The prime minister earns enough to buy a HDB public housing flat in one to two months.

How many years do you have to work to pay for a HDB flat? Do you get any CPF pension savings left after that?

The prime minister earns enough every two months to buy a HDB flat. But your HDB flat will have zero value at the end of 99-years.

Who did you vote for?

(The above’s original post on Facebook can be read here.)

But does the Singapore prime minister not know how to give a straight answer?

A week later, on 17 September, the Singapore government posted an accusation against Singaporeans on its Factually website.

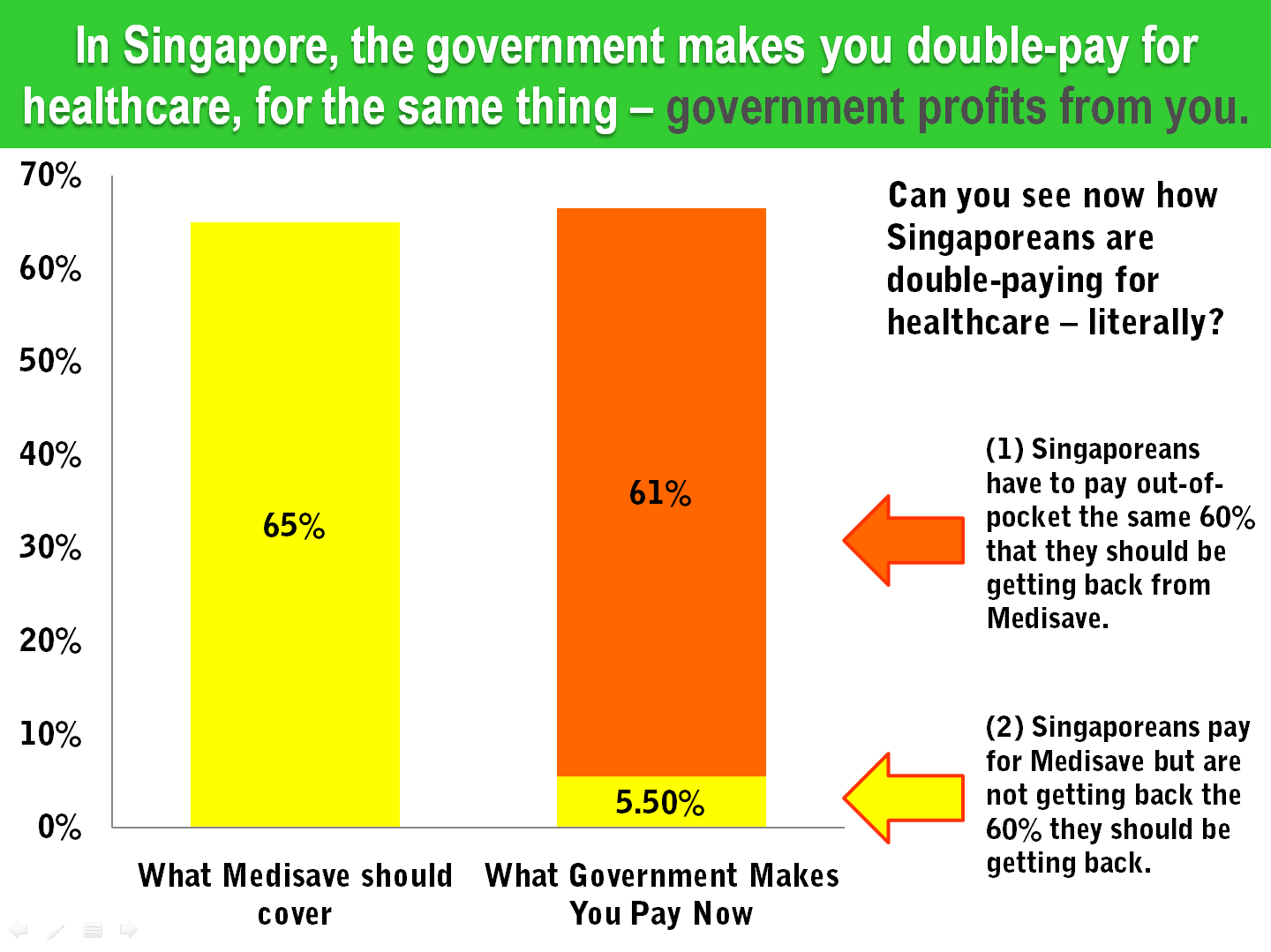

But isn’t this what we have been asking all along? What is the prime minister’s national bonus? What is his AVC? Also, what is his special variable payment? Why didn’t the government talk about the special variable payment (SVC) in its latest article? This SVC component is also stated in the 2011 White Paper they talked about.

The Factually website ended by saying that the prime minister “does receive the National Bonus” (emphasis mine). But it does not want to reveal how much the prime minister’s exact national bonus is. If so, isn’t the government “not upfront about how ministerial salaries are calculated”, which was what the government’s article claimed to want to clarify?

Why claim to “clarify” without providing the actual breakdown and calculations?

Also, the Factually website only said that, “The Prime Minister’s norm salary is set at two times that of an MR4 Minister. His $2.2 million annual salary includes bonuses.” But do you know what the government does not say in this latest article? This “norm” salary is actually only “the mid-point of the range of bonuses payable and describes a situation where individual performance is good and targets for the National Bonus indicators are met”. This is stated inside the White Paper too. So why doesn’t the government explicitly say this in the latest article?

So, this S$2.2 million is the so-called “norm salary”. We do not just want to know how much his “norm” salary is. How much is his total salary exactly every year, after accounting for the (1) national bonus, (2) AVC, and (3) SVC? This is what we want to know. And do you know there is actually no stated limit as to how high the SVC can be?

When you are paid a salary, do you ask to be paid a “norm” salary, or do you want to know your full salary, including the bonuses?

Some online news sites have calculated this to be between S$2.5 million and S$3 million, based on how much they estimate the national bonus to be, based on the formula, as also stated in the White Paper (and not the S$2.2 million “norm” salary, whatever that means anyway). I have estimated it to be about S$2.53 million, and this is not yet including the special variable payment on the years they are paid.

Similarly, it has been estimated that the prime minister earns a total of 10 to 11 months of bonuses/AVC/SVP, at least. Why can’t the Factually website just state exactly how much the prime minister’s bonus is, instead of only saying that he is paid a national bonus, without saying how much it is?

Why can’t the government be upfront about it on the Factually website? Why put up information to claim to clarify without providing actual facts to clarify?

The government has zero right to deride other websites when it itself is not completely upfront and fully transparent about this information.

Tell us how much the prime minister’s (1) national bonus, (2) AVC, and (3) SVC is.

Tell us how much his total salary is for all the years he has been paid. Do not give half-baked answers.

Why does the Singapore PAP government not want to be completely upfront? Why does the Singapore PAP government choose to be non-transparent, like how it deals with Singaporean’s CPF pension and HDB public housing?

Does the Singapore PAP government take Singaporeans for fools?

(The above’s original post on Facebook can be read here.)

In summary, the following chart shows the important facts that the Singapore government chose to leave out in its “clarifications” on the ministerial salaries on the Factually website.

Can the PAP not answer a simple question? Or do they not want to answer? Is it that hard to be transparent?

Instead of chastising others for trying to work out estimates, the PAP government should come clean with the actual total salary that the Singapore prime minister and other ministers are earning. Why try to defend itself without without telling the truth?

It is not difficult to answer. Question is, why does the government beat around the bush? Is it very embarrassing if Singaporeans were to know?

Ministerial salaries are public information, which the government should provide plainly. What is the prime minister’s actual total salary, and that of the other ministers?

On 1 October, Singapore’s deputy prime minister Teo Chee Hean said in parliament: “all the components [of the salary for entry-level ministers] are within the framework of the S$1.1 million that was put in place in 2012.”

Chee Hean also said: “The salary structure is totally transparent. There are no hidden salary components or perks.”

Now, the S$1.1 million salary is calculated based on the following components:

- Fixed component I: 12 months salary

- Fixed component II: 13th-month bonus

- Variable component I: 3 months Performance Bonus (PB)

- Variable component II: 3 months National Bonus (NB)

- Variable component III: 1 month Annual Variable Component (AVC)

- TOTAL: 20 MONTHS (13 months fixed component + 7 months variable component)

*****

But note, the above is only for illustration purposes, because the total number of bonuses that the ministers can receive are higher:

- Performance Bonus (PB): up to 6 months

- National Bonus (NB): up to 6 months

- Annual Variable Component (AVC): up to 1.5 month

- Special Variable Payment (SVC): no stated limit

- TOTAL APPLICABLE BONUSES:

- not including SVC: up to 13.5 months

- including SVC: unlimited*

- TOTAL APPLICABLE SALARY:

- not including SVC: up to 26.5 months

- including SVC: unlimited*

*There is no limit to the SVC based on the current publicly available information, unless the government is willing to provide more information.

>>>>>

Chee Hean also revealed that from 2013 to 2017:

- The Singapore ministers earned National Bonuses (NB) of 3.4 to 4.9 months, with an average of 4.1 months over the 5-year period.

- On 10 September, Singapore’s prime minister Hsien Loong also revealed that between 2013 and 2017, the ministers earned Performance Bonuses (PB) of 3 to 6 months, with an average of 4.3, 4.2, 4.4, 4.3 and 4.1 months in 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016 and 2017, respectively. The average is 4.3 months over the 5-year period.

- On 1 October, Chee Hean also revealed that from 2013 to 2017, the ministers earned an AVC of 0.95 to 1.5 months, with an average of 1.3 months over the 5-years period.

Questions:

- But how much exactly is the average National Bonus (NB) for each year? It is not known, or if it was shared in parliament on 1 October, it was not reported.

- Also, how much has been the total salaries of each of the ministers since 1959, and what were the exact breakdowns?

*****

Using the lower limit, average and upper limit bonuses/AVC of each of the components, the total salary for an entry-level minister is estimated as according:

(i) Lower Limit: 13 months (fixed component) + 3.4 months (NB) + 3 months (PB) + 0.95 months (AVC) (TOTAL: 20.35 months)

==> S$1.11925 MILLION

(ii) Average: 13 months (fixed component) + 4.1 months (NB) + 4.3 months (PB) + 1.3 months (AVC) (TOTAL: 22.7 months)

==> S$1.2485 MILLION

(iii) Upper Limit: 13 months (fixed component) + 4.9 months (NB) + 6 months (PB) + 1.5 months (AVC) (TOTAL: 25.4 months)

==> S$1.397 MILLION

As such, from 2013 to 2017, an entry-level minister never earns just only S$1.1 million, he or she always earns higher than S$1.1 million. From 2013 to 2017, the salary of an entry-level minister ranges from an estimated S$1.12 million to S$1.40 million.

*****

Similarly, for the deputy prime ministers, the total salary is estimated as according:

(i) Lower Limit: 13 months (fixed component) + 3.4 months (NB) + 3 months (PB) + 0.95 months (AVC) (TOTAL: 20.35 months)

==> S$1.902725 MILLION

(ii) Average: 13 months (fixed component) + 4.1 months (NB) + 4.3 months (PB) + 1.3 months (AVC) (TOTAL: 22.7 months)

==> S$2.12245 MILLION

(iii) Upper Limit: 13 months (fixed component) + 4.9 months (NB) + 6 months (PB) + 1.5 months (AVC) (TOTAL: 25.4 months)

==> S$2.3749 MILLION

As such, from 2013 to 2017, the deputy prime ministers never earn just only S$1.87 million, they always earn higher than S$1.87 million. From 2013 to 2017, the salaries of the deputy prime ministers range from an estimated S$1.90 million to S$2.37 million.

*****

The Singapore prime minister does not get a Performance Bonus (PB), but he gets twice the National Bonus (NB). As such, again based on the lower limit, average and upper limit bonuses/AVC of each of the component, the total salary for the prime minister is estimated as according:

(i) Lower Limit: 13 months (fixed component) + 6.8 months (NB) + 0.95 months (AVC) (TOTAL: 20.75 months)

==> S$2.2825 MILLION

(ii) Average: 13 months (fixed component) + 8.2 months (NB) + 1.3 months (AVC) (TOTAL: 22.5 months)

==> S$2.475 MILLION

(iii) Upper Limit: 13 months (fixed component) + 9.8 months (NB) + 1.5 months (AVC) (TOTAL: 24.3 months)

==> S$2.673 MILLION

As such, from 2013 to 2017, the prime minister never earns just only S$2.2 million, he has always earned higher than S$2.2 million. From 2013 to 2017, the salary of the prime minister ranges from an estimated S$2.28 million to S$2.67 million.

*****

Without the exact breakdowns according to each year, these are the best estimates that we can come out with.

Why does Chee Hean insists on using S$1.1 million for illustration when from 2013 to 2017, an entry-level minister clearly earns more than that? Why does the Singapore government insists on saying that the prime minister earns S$2.2 million when from 2013 to 2017, he clearly earns more than that?

Chee Hean also said: “The salary structure is totally transparent. There are no hidden salary components or perks.”

But do you see the problem? Until now, we still do not know exactly how much the prime minister and ministers were paid in TOTAL. Why does the PAP government insists on not being “totally transparent” with this information?

And if Singaporeans are forced to estimate the total salaries based on the incomplete information that is given, does the PAP government have a right to say that Singaporeans are spreading falsehoods, when it is the PAP that has been non-transparent?

>>>>>

But here is one last thing: do you know that there is a Special Variable Payment (SVC) which the ministers can earn, which has no stated limit, which in theory can be an infinite amount?

This SVC has never been disclosed.

WP should ask this question in parliament.

>>>>>

Now, look back at what Chee Hean said (which I quoted at the start of this Facebook post on 1 October). Knowing all these now, in Chee Hean’s words, “what do you think” of what he said?

Chee Hean called the Worker’s Party disingenuous. But who is the one being disingenuous?

(The above’s original post on Facebook can be read here.)

*****

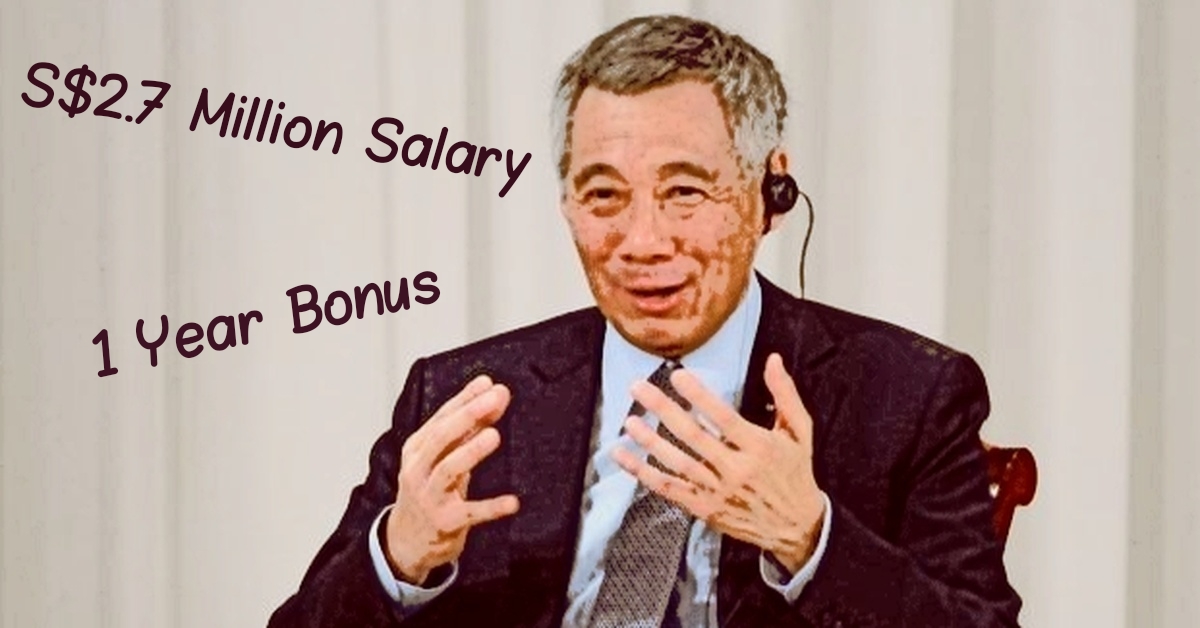

In summary, from 2013 to 2017, Singapore’s ministers earned an average of 9.7 months of bonuses. Over the same period, the Singapore prime minister earned as much as more than 12 months in bonuses, or more. In one year, the prime minister can earn as much as S$2.7 million, or more than two years worth of salary (but this is still not including his Special Variable Payment (SVP), and no one knows how much this is as there is no stated limit as to how many months the SVP is).

The prime minister earns an average of as much as S$220,000 a month (or more) but a cleaner earns only as low as S$1,060 a month. The average starting salary of a polytechnic graduate is only S$2,200 a month, and Singapore’s median wage is only S$3,749 a month (not including CPF). The prime minister earns nearly 60 times what a median wage earner earns, 100 times more than a polytechnic graduate and nearly 210 times more than a cleaner. It would take a cleaner more than 210 years to earn what the prime minister earns in a year, or more than 5 working lifetimes. The prime minister takes only less than an hour to earn what a cleaner earns.

A cleaner in Singapore will only earn 2 weeks of bonus (starting 2020). The Singapore prime minister earns as much as more than 12 months of bonuses (or 1 whole year) between 2013 and 2017.

Is this acceptable?

Figure: 2011 White Paper

Finally, Singapore deputy prime minister Teo Chee Hean said: “The salary structure is totally transparent. There are no hidden salary components or perks.”

Then, what is the Special Variable Payment? And why is there no stated limit on how many months the Special Variable Payment is?

Note that the Singapore PAP ruling regime has not disclosed what the TOTAL salaries for the Singapore prime minister and the ministers are.

This is because of a Special Variable Payment (SVC). The PAP has not revealed how many months of this SVC bonus the ministers can get. In fact, there is no stated limit on the number of months the SVC can go up to.

This means that in theory, the SVC has no limit and the prime minister and each minister can earn even possibly tens of millions of dollars per person.

In fact, when the PAP tried to “clarify” on its Factually website, it was only willing to say that the prime minister’s “norm” salary is S$2.2 million, without saying that when including the other bonuses, that it could be as high as S$2.7 million between 2013 and 2017, and even more when including the SVC. In fact, Factually only said that it is not true that the prime minister gets paid “up to $4.5 million a year”. So does it mean that it could be true that he gets paid up to S$4.4 million or up to S$10 million, or more?

The only way for the PAP to account to Singaporeans is to be fully transparent and disclose how much the total salaries are for the prime minister and minsters, including the complete breakdown. If not, it has zero right to shame Singaporeans who try to come out with estimates, when it is the one who obviously feels too ashamed to tell Singaporeans the exact figures.

It has been one month since The Worker’s Party asked this question in parliament and to date, we still have no complete answer. Is the PAP so ashamed that it cannot come clean with this information, which should be public information in the first place?

Deputy prime minister Chee Hean called The Worker’s Party disingenuous, but it is the PAP which has been disingenuous by not being completely upfront. Whoever wrote the Factually website is also complicit.

What is the total salary of the prime minister and ministers, and what are the complete breakdowns? How much SVC did the prime minister and each minister get every year since the SVC started?

(The above’s original post on Facebook can be read here.)